If you pay just a little attention to this topic surfing the internet, it becomes immediately evident that public toilets are a subject very much appreciated by contemporary architects and architecture magazines. Even though the theme may still be considered a taboo and ‘the dedicated place’ may traditionally be imagined as a hidden, almost invisible corner, public loos have become a design issue all over developed countries and many architects have been asked to design high-tech, iconic and [above all] recognizable public toilets.

One of the indicators that show the rising interest around sanitation facilities is the admission of loos within the projects competing to international awards (even though a dedicated category does not exist yet), and the number of sanitation projects that received an architectural award in the last 10 years: [1] the sculpture-shaped Mirò-Rivera Architects Trail Restroom in Texas was shortlisted in the Energy, waste & recycling Category at the World Architecture Festival 2008; [2] the evanescent golden mesh-box by Gort Scott Architects for Wembley WC Pavilion was shortlisted in the Civic, Culture & Sport category at the New London Awards 2014; [3] the dragon-shaped Kumototo toiletsby StudioPacific won the NZIA Wellington Architecture Awards 2012 in the Public Category, just to mention few examples.

As it often happens when dealing with values of civil society, Scandinavian countries, and particularly Norway, seem to attach great importance to public sanitation. Spread along wild national tourist roads and highways, multiple examples of public restrooms show not only a high commitment to the provision of public facilities for travelers, but also the idea that even a small sanitation pavilion is worth an accurate design no matter how far and isolated from a great audience it will be.

([4] Flotane rest stop, L J B architects, [5] Aurland public toilets, Saunders arkitektur & Wilhelmsen arkitektur , [6] Akkarvik Roadside Reststop, Manthey Kula architects, [7] Jektvik Ferry Quay Area, Carl-Viggo Hølmebakk and Manthey Kula, etc.).

Even when more accessible and handy, valuable natural landscapes are a scenario where public restrooms can be found quite commonly.

Beach fronts ([8] Sydney’s

Cook-park-amenities, Fox Johnston architects), urban parks ([9]

Public Toilets in the Tête d’Or Park, Lyon, Jacky Suchail Architecture Urbanisme), lake shores ([10] the above mentioned Mirò-Rivera Architects

Trail Restroom near the Lady Bird Lake in Austin, Texas), and many other natural locations in the world have been equipped with low impact pavilions aimed at providing visitors with public basic and more advanced facilities (lavatories, showers, changing tables, shadowy benches etc.). Rural Studio even expanded this issue transforming countryside restrooms into a research theme and realizing in Perry Lakes Park, Alabama, three very peculiar prototypes of toilets where

‘the tall’ one allows a pensive glance of the sky while using the facility,

‘the long’ one facilitates the dialog with nature incorporating a tree into the toilet, and

‘the mound’ one offers an underground experience.

Sometimes, when restrooms are combined with other, more complex spaces, the result can be an ambitious, organic building like Reiulf Ramstad Architects’ Havøysund Tourist Route, Norway [12], aimed at enhancing the experience of nature and equipped with open kitchen, bike shed, parking and fireplace, or the Hansteerds Architectuur’s Cemetery entrance pavilion in Blankenberge, Belgium [13], a wooden structure finished with oriented strand boards in the interior and horizontal wooden slats on the outside walls.

12

13

Despite the fact that toilets are technological elements that require, especially [but not exclusively] in rural and isolated areas, a complex and independent collection+storage+disposal system, typically very poor information is provided on those technological aspects and many of the previous examples are very much centered on the iconic value of the architectural design:

the Kumototo example in New Zealand [14] is the most explicit in its aim of surprising visitors and bewildering users, but also the small Public Toilet Unit by Schleifer & Milczanowski Architekci in Poland [15], with its round, segmented, asymmetrical shape is a very recognizable object in the historical center of Gdańsk; Gramazio Kohler Architects’ Public Toilets in Uster, Switzerland [16] plays with the design of the box’s façade, made with brilliant, folded, vertically arranged colored aluminum strips; Hiroshima Park [17]Future Studio’s restrooms uses triangular shape, color and round openings to create a series of glowing UFOs in Hiroshima city parks; Niedersachsen Motorway Toilets by gruppeomp architekten bda [18] in Germany uses a colored pattern derived from the city plan to emphasize the toilet’s outer walls and make them well visible in the distance.

Sometimes, public loos are explicitly utilized as places where art can freely express herself or, on the other hand, as places that can be newly interpreted through the lens of art.

Daigo Ishii + Future-scape Architects’ evocative and poetic House of Toilet in Japan [19] was part of Setouchi Art Triennale 2013 due to its design based on cuts aimed at ideally connecting the building with the rest of the world and at evoking seasonal milestones in Japanese culture; Itabu Toilet in Ichihara, Japan, by Sou Fujimoto [20], is an installation presented during the city’s art festival, where a toilet is placed in a glass box standing in the middle of a garden, providing occupants with a serene bucolic view while using the facility. Monica Bonvicini’s Don’t miss a sec’, a one-way glass box that allows users to continue seeing the outside world while not being seen [21], was temporarily installed in a crowded street adjacent to the Basel Art Fair in London and referred to the urge not to miss a thing during cultural urban events. Last but not least, the famous Kawakawa Toilets in New Zealand by Austrian artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser [22] is a Gaudì-style masterpiece of how a 40-year-old toilet facility can be transformed with tiles, sculptures, old bottles and broken mirrors.

But the world of fine arts is not the only one who has discovered the powerful potential of toilets as a design catalyst. The private sector as well has identified restrooms as places where people don’t want to hide anymore but, on the contrary, where they want to experience peculiar and, possibly, stylish private moments. For instance, Berschneider architect’s Toilettenhäuschen in Lauterhofen golf club in Germany [23] as well as Toilettenhäuschen II [24] are two examples of detailed design and fashionable finishing applied to a sanitary facility in the middle of [a very exclusive] spot of nature.

23

24

CONCLUSIONS

At the end of this long overview of contemporary public toilets, what catches my eye is that these interventions are often isolated, single structures. Even when two or more restrooms are designed to be built closely, they still seem to represent much more the satisfaction of a creative act rather that the attempt to solve a problem. The way press and websites present these buildings draws the attention exclusively to the specific esthetic features of each facility, as if they were art pavilions. Even the architect’s own descriptions of their project seldom mention cost or technical aspects and focuses on materials, light and finishing.

From my point of view this lack of information on technological aspects, which may be a consequence of an actual lack of technological innovation, represents a lost opportunity for designers and clients: having the chance to investigate a crucial sector as the sanitation one in isolated off-the-grid contexts should also be the occasion to experiment new, sustainable, innovative solutions not only for the decoration but also for the technological aspects of toilets, as wastes collection and disposal, water supply and dispersal, self sustainability, energy supply, etc.

This entails that no one of these many examples of public sanitation facilities has been conceived taking into consideration possible adaptations to low income countries. Again, a lost occasion, given that developing countries are in desperate need of innovative solutions to deal with sanitation problems.

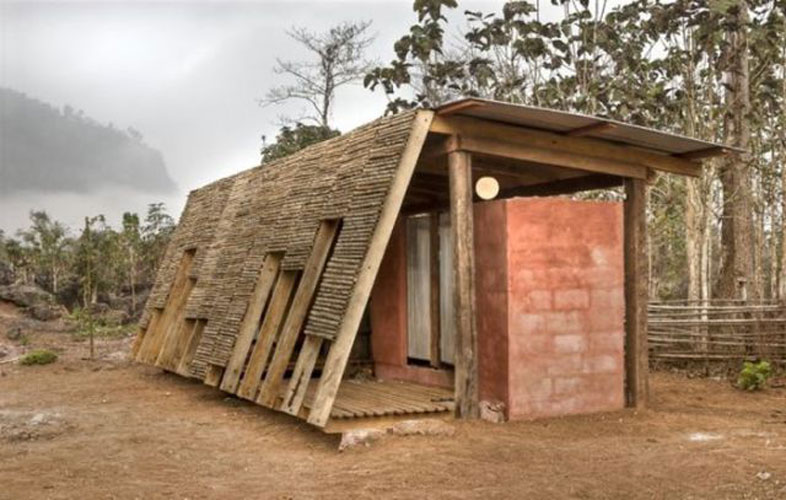

A couple of examples can, nonetheless, be mentioned as isolated exceptions: TYIN’s Safe Haven Bathhouse [25] in Thailand, a locally adapted community toilet where drainage, rainwater harvesting, sewage and wastes management are thoroughly designed and clearly explained; and Delwara community toilets [26], a project by vir.mueller architects for a village in India, where sanitation facilities have been combined with a sort of public space where people can gather and establish neighboring relations while fetching water or washing clothes.

25

26

In the end, even if the growing interest that architecture shows for sanitation facilities is a positive sign, a lot has still to be done in order to move this attention from the shape to the essence of the subject: far from being a fashionable design object, toilets are a very crucial, basic, vital need for 2/3 of the world, and maybe the time has come for architects to acknowledge this reality and cope with it.

ET

Public toilets in contemporary architecture: coups de théâtre or real issues?

If you pay just a little attention to this topic surfing the internet, it becomes immediately evident that public toilets are a subject very much appreciated by contemporary architects and architecture magazines. Even though the theme may still be considered a taboo and ‘the dedicated place’ may traditionally be imagined as a hidden, almost invisible corner, public loos have become a design issue all over developed countries and many architects have been asked to design high-tech, iconic and [above all] recognizable public toilets.

One of the indicators that show the rising interest around sanitation facilities is the admission of loos within the projects competing to international awards (even though a dedicated category does not exist yet), and the number of sanitation projects that received an architectural award in the last 10 years: [1] the sculpture-shaped Mirò-Rivera Architects Trail Restroom in Texas was shortlisted in the Energy, waste & recycling Category at the World Architecture Festival 2008; [2] the evanescent golden mesh-box by Gort Scott Architects for Wembley WC Pavilion was shortlisted in the Civic, Culture & Sport category at the New London Awards 2014; [3] the dragon-shaped Kumototo toiletsby StudioPacific won the NZIA Wellington Architecture Awards 2012 in the Public Category, just to mention few examples.

1

2

3

As it often happens when dealing with values of civil society, Scandinavian countries, and particularly Norway, seem to attach great importance to public sanitation. Spread along wild national tourist roads and highways, multiple examples of public restrooms show not only a high commitment to the provision of public facilities for travelers, but also the idea that even a small sanitation pavilion is worth an accurate design no matter how far and isolated from a great audience it will be.

([4] Flotane rest stop, L J B architects, [5] Aurland public toilets, Saunders arkitektur & Wilhelmsen arkitektur , [6] Akkarvik Roadside Reststop, Manthey Kula architects, [7] Jektvik Ferry Quay Area, Carl-Viggo Hølmebakk and Manthey Kula, etc.).

4

5

6

7

Beach fronts ([8] Sydney’s Cook-park-amenities, Fox Johnston architects), urban parks ([9] Public Toilets in the Tête d’Or Park, Lyon, Jacky Suchail Architecture Urbanisme), lake shores ([10] the above mentioned Mirò-Rivera Architects Trail Restroom near the Lady Bird Lake in Austin, Texas), and many other natural locations in the world have been equipped with low impact pavilions aimed at providing visitors with public basic and more advanced facilities (lavatories, showers, changing tables, shadowy benches etc.). Rural Studio even expanded this issue transforming countryside restrooms into a research theme and realizing in Perry Lakes Park, Alabama, three very peculiar prototypes of toilets where ‘the tall’ one allows a pensive glance of the sky while using the facility, ‘the long’ one facilitates the dialog with nature incorporating a tree into the toilet, and ‘the mound’ one offers an underground experience.

8

9

10

11

Sometimes, when restrooms are combined with other, more complex spaces, the result can be an ambitious, organic building like Reiulf Ramstad Architects’ Havøysund Tourist Route, Norway [12], aimed at enhancing the experience of nature and equipped with open kitchen, bike shed, parking and fireplace, or the Hansteerds Architectuur’s Cemetery entrance pavilion in Blankenberge, Belgium [13], a wooden structure finished with oriented strand boards in the interior and horizontal wooden slats on the outside walls.

12

13

Despite the fact that toilets are technological elements that require, especially [but not exclusively] in rural and isolated areas, a complex and independent collection+storage+disposal system, typically very poor information is provided on those technological aspects and many of the previous examples are very much centered on the iconic value of the architectural design:

the Kumototo example in New Zealand [14] is the most explicit in its aim of surprising visitors and bewildering users, but also the small Public Toilet Unit by Schleifer & Milczanowski Architekci in Poland [15], with its round, segmented, asymmetrical shape is a very recognizable object in the historical center of Gdańsk; Gramazio Kohler Architects’ Public Toilets in Uster, Switzerland [16] plays with the design of the box’s façade, made with brilliant, folded, vertically arranged colored aluminum strips; Hiroshima Park [17]Future Studio’s restrooms uses triangular shape, color and round openings to create a series of glowing UFOs in Hiroshima city parks; Niedersachsen Motorway Toilets by gruppeomp architekten bda [18] in Germany uses a colored pattern derived from the city plan to emphasize the toilet’s outer walls and make them well visible in the distance.

14

15

16

17

18

Sometimes, public loos are explicitly utilized as places where art can freely express herself or, on the other hand, as places that can be newly interpreted through the lens of art.

Daigo Ishii + Future-scape Architects’ evocative and poetic House of Toilet in Japan [19] was part of Setouchi Art Triennale 2013 due to its design based on cuts aimed at ideally connecting the building with the rest of the world and at evoking seasonal milestones in Japanese culture; Itabu Toilet in Ichihara, Japan, by Sou Fujimoto [20], is an installation presented during the city’s art festival, where a toilet is placed in a glass box standing in the middle of a garden, providing occupants with a serene bucolic view while using the facility. Monica Bonvicini’s Don’t miss a sec’, a one-way glass box that allows users to continue seeing the outside world while not being seen [21], was temporarily installed in a crowded street adjacent to the Basel Art Fair in London and referred to the urge not to miss a thing during cultural urban events. Last but not least, the famous Kawakawa Toilets in New Zealand by Austrian artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser [22] is a Gaudì-style masterpiece of how a 40-year-old toilet facility can be transformed with tiles, sculptures, old bottles and broken mirrors.

19

20

21

22

But the world of fine arts is not the only one who has discovered the powerful potential of toilets as a design catalyst. The private sector as well has identified restrooms as places where people don’t want to hide anymore but, on the contrary, where they want to experience peculiar and, possibly, stylish private moments. For instance, Berschneider architect’s Toilettenhäuschen in Lauterhofen golf club in Germany [23] as well as Toilettenhäuschen II [24] are two examples of detailed design and fashionable finishing applied to a sanitary facility in the middle of [a very exclusive] spot of nature.

23

24

CONCLUSIONS

At the end of this long overview of contemporary public toilets, what catches my eye is that these interventions are often isolated, single structures. Even when two or more restrooms are designed to be built closely, they still seem to represent much more the satisfaction of a creative act rather that the attempt to solve a problem. The way press and websites present these buildings draws the attention exclusively to the specific esthetic features of each facility, as if they were art pavilions. Even the architect’s own descriptions of their project seldom mention cost or technical aspects and focuses on materials, light and finishing.

From my point of view this lack of information on technological aspects, which may be a consequence of an actual lack of technological innovation, represents a lost opportunity for designers and clients: having the chance to investigate a crucial sector as the sanitation one in isolated off-the-grid contexts should also be the occasion to experiment new, sustainable, innovative solutions not only for the decoration but also for the technological aspects of toilets, as wastes collection and disposal, water supply and dispersal, self sustainability, energy supply, etc.

This entails that no one of these many examples of public sanitation facilities has been conceived taking into consideration possible adaptations to low income countries. Again, a lost occasion, given that developing countries are in desperate need of innovative solutions to deal with sanitation problems.

A couple of examples can, nonetheless, be mentioned as isolated exceptions: TYIN’s Safe Haven Bathhouse [25] in Thailand, a locally adapted community toilet where drainage, rainwater harvesting, sewage and wastes management are thoroughly designed and clearly explained; and Delwara community toilets [26], a project by vir.mueller architects for a village in India, where sanitation facilities have been combined with a sort of public space where people can gather and establish neighboring relations while fetching water or washing clothes.

25

26

In the end, even if the growing interest that architecture shows for sanitation facilities is a positive sign, a lot has still to be done in order to move this attention from the shape to the essence of the subject: far from being a fashionable design object, toilets are a very crucial, basic, vital need for 2/3 of the world, and maybe the time has come for architects to acknowledge this reality and cope with it.

ET

Tags: